ChatGPT-powered Robot Chef

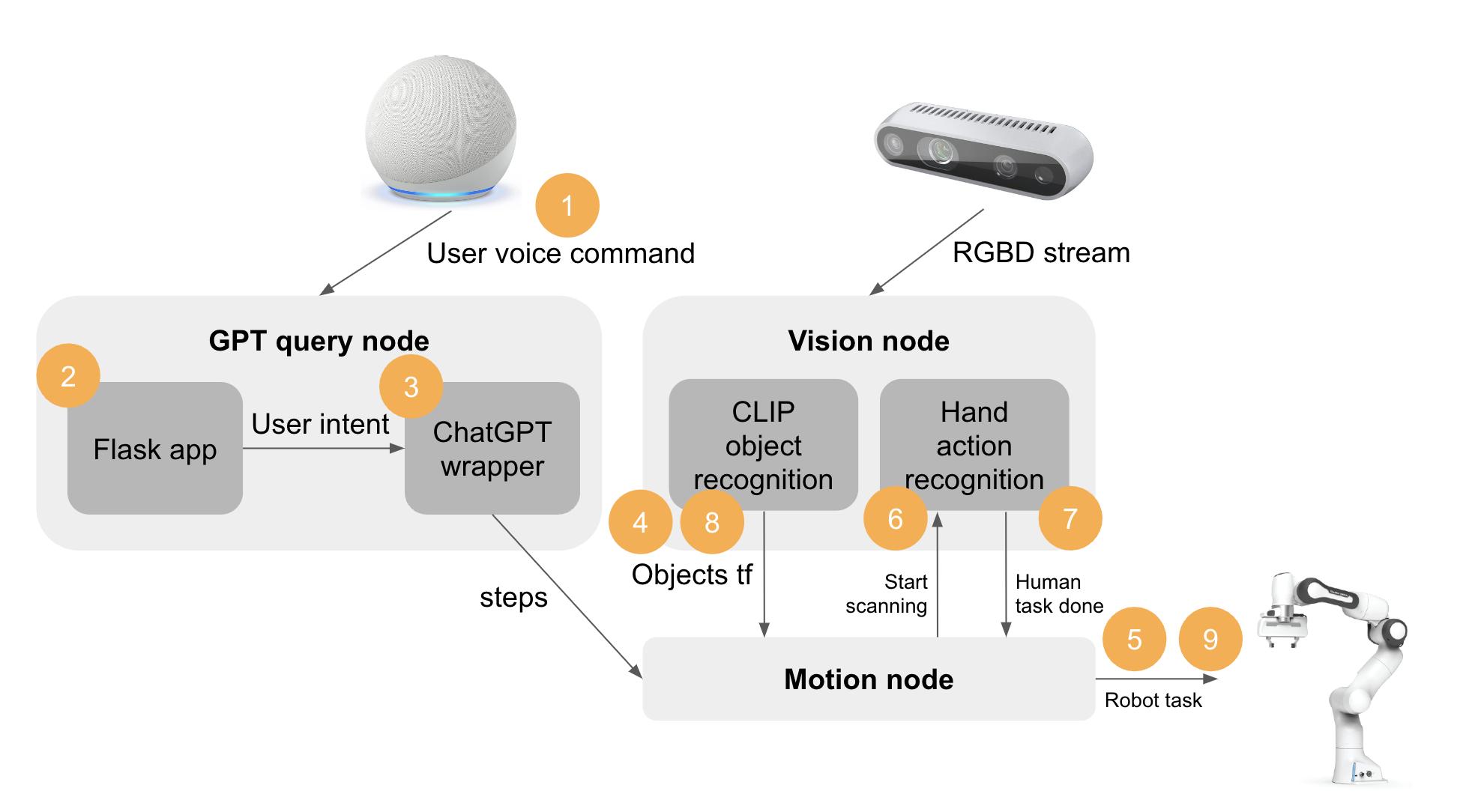

This project is a system that enables voice-controlled, robot-assisted cooking. The system utilizes a custom Alexa skill to process user voice commands and a Flask app to generate recipe steps through ChatGPT. Object detection using a RealSense camera and the CLIP model allows the system to recognize objects in the kitchen and adjust recipe steps accordingly. The robot arm executes the steps autonomously, while a hand-action recognition model based on MediaPipe provides the necessary feedback to ensure collaboration between human and robot in completing the cooking tasks. This system contributes to home automation technology and showcases the integration of machine learning, computer vision, and robotics in real-world applications.

Video Demo

System Architecture

Alexa Custom Skill

To enable users to interact with this system more intuitively and conveniently, I built a custom Alexa skill that enables users to control the system through voice commands. The Alexa Developer console was used to build and deploy the custom skill on an Alexa dot, which converts audio to text and extracts the user’s intent, which refers to the recipe they want to cook. Once the intent is extracted, the Alexa custom skill sends an HTTP request to a local Flask app, which would then process the request with ChatGPT to generate recipe steps that the robot arm can execute.

ChatGPT Query

Overview

To process the user’s intent and generate the recipe steps, the Flask app uses ChatGPT, a state-of-the-art language model that can process natural language input and generate text outputs. The Flask app builds up a prompt that includes example recipes, detected items using CLIP, and the current user intent/instruction. This prompt is then fed into ChatGPT, which generates a sequence of recipe steps that the robot arm can execute. By leveraging ChatGPT’s advanced language processing capabilities, the system can provide users with detailed, context-sensitive instructions that take into account the available ingredients, the user’s intent, and the current state of the kitchen. This allows the system to generate highly personalized and adaptive cooking instructions that are tailored to the specific needs of each user.

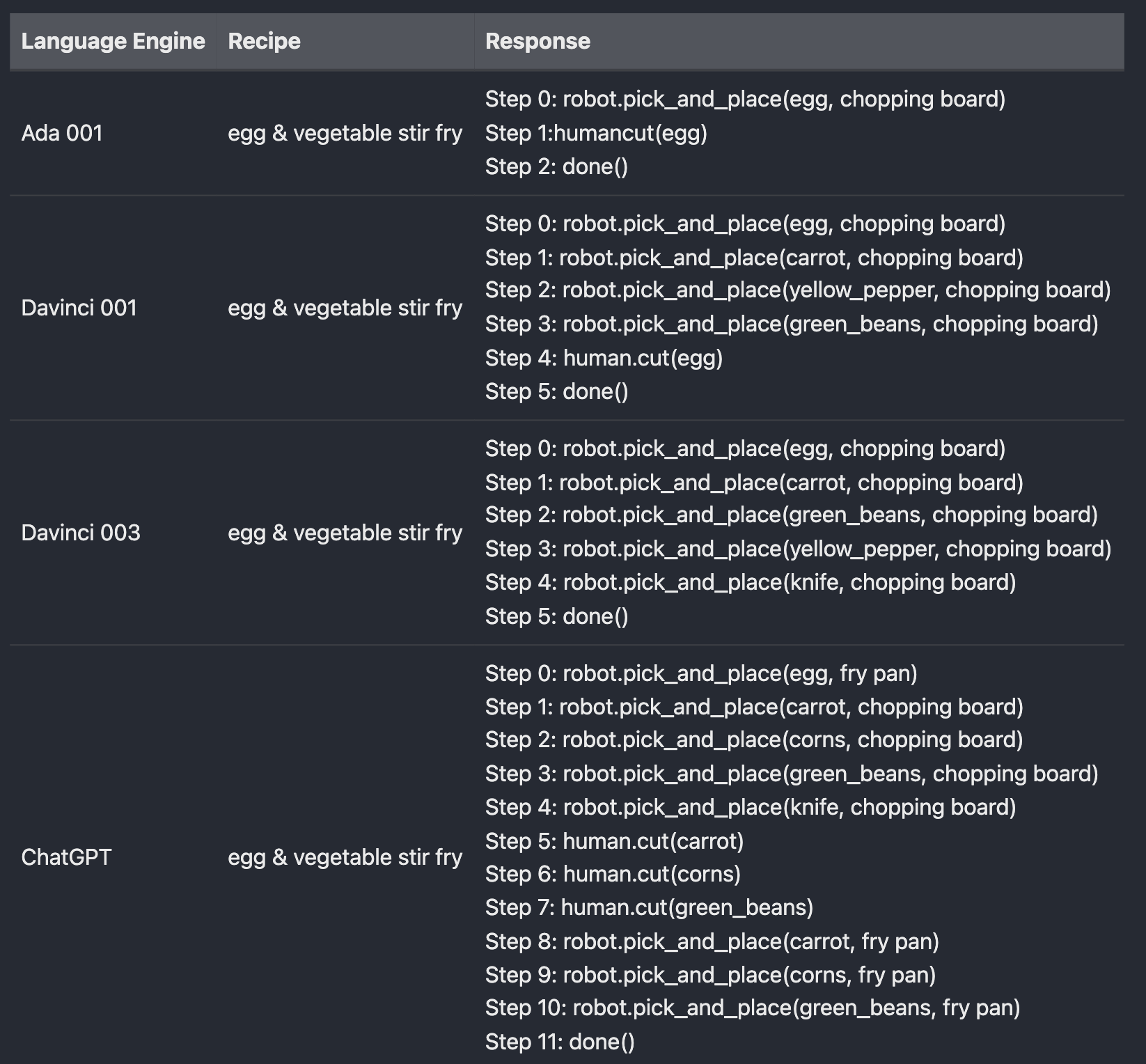

Comparison with other GPT3 engines

During the development of the system, I evaluated several language models, including GPT-3 engines from OpenAI such as Ada 001, Davinci 001, and Davinci 003. We implemented a comparison test that utilized a simulated pick and place example code from the open-source SayCan project. The test involved building a collection of options based on the items available in the kitchen and then feeding them into the different language models to obtain scores via text completion. The highest-scoring action was then selected and added to the current context, with the process repeating until the recipe was complete. While the GPT-3 engines worked well for simple recipes, they struggled to handle more complicated recipes, particularly those that required human action. After comparing the results of each engine, we found that ChatGPT outperformed the others, particularly on more complex recipes. A comparison chart between all the engines and the result from ChatGPT is included below, highlighting the superiority of ChatGPT in handling complex recipe instructions.

ChatGPT wrapper

It is worth noting that at the time of this project, the ChatGPT API was not yet released by OpenAI. Therefore, a ChatGPT wrapper was used to enable the integration of ChatGPT with the system. This wrapper allows the use of ChatGPT within a Python environment.

Object Detection with CLIP

Comparison with traditional object detection methods

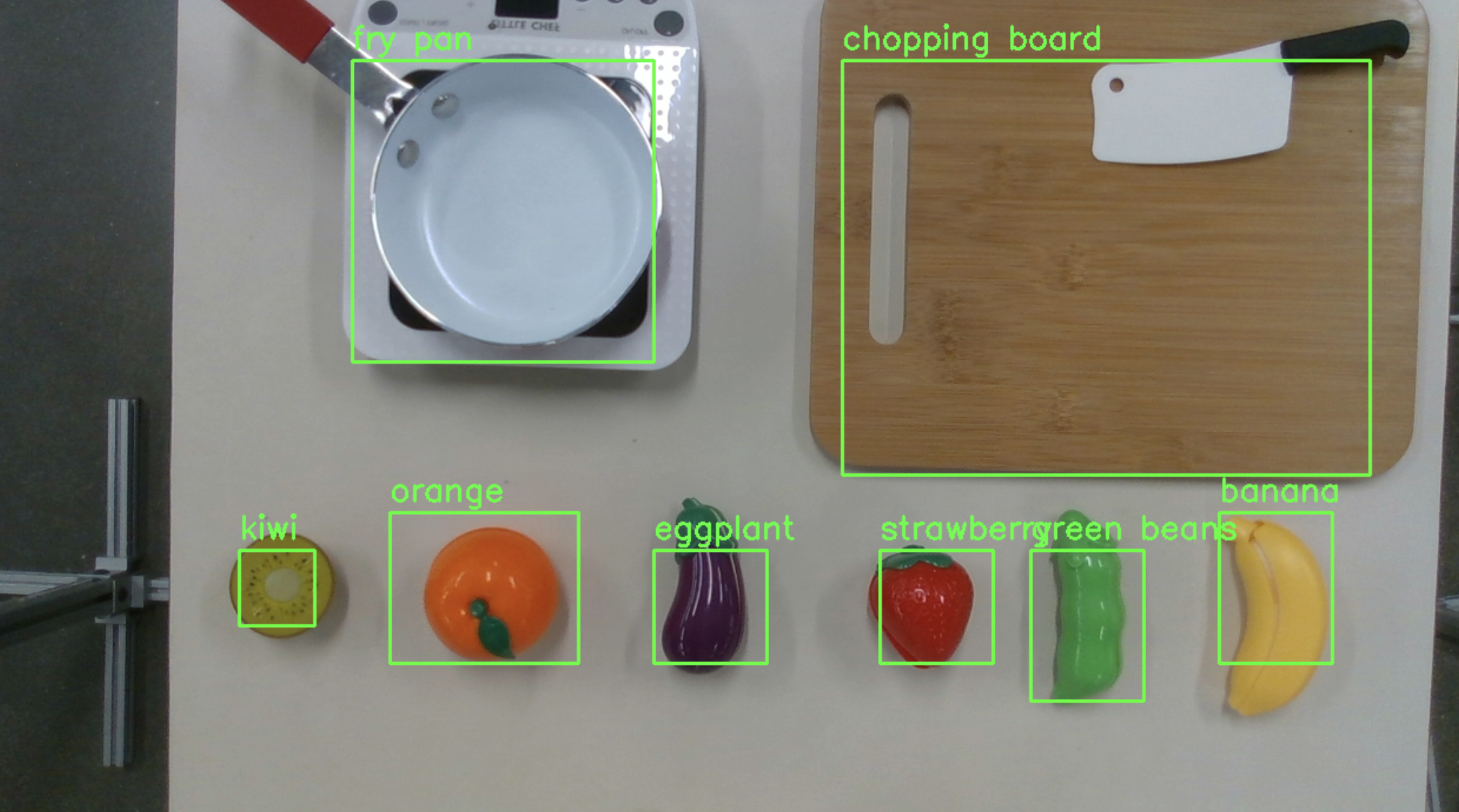

For object detection, the system uses a RealSense D435i camera and a machine learning model called CLIP. Unlike other state-of-the-art object detection models like DETR and YOLO v5, CLIP is trained on a massive dataset of 400 million (image, text) pairs, making it capable of recognizing out-of-vocabulary objects without the need for additional labeled data. Since CLIP can recognize objects based on their textual descriptions, it can also take into account different variations and synonyms of the same object, leading to a more robust detection performance. For example, we can ask CLIP to find a “red apple” or “chopped onion”. The 3D location of objects in the kitchen is provided by CLIP, which produces center object bounding boxes and uses depth information from the RealSense camera. Initially, I experimented with other object detection models but found that they couldn’t recognize out-of-vocabulary objects without fine-tuning on every kitchen’s novel objects, which was not practical. In contrast, CLIP’s ability to recognize a wide range of objects without the need for additional labeling made it a more general and usable solution for the system.

Implementation of CLIP for multiple objects

While the original CLIP model only performs image classification for a single object, we need to perform object detection for multiple objects in our kitchen.

To utilize CLIP for object detection, I followed a tutorial called Zero Shot Object Detection with OpenAI’s CLIP. The basic idea behind this approach is to break an image into many small patches, and pass a window over these patches, generating an image embedding for each unique window. We can then calculate the similarity between these patch image embeddings and our class label embeddings, returning a score for each patch. After calculating the similarity scores for every patch, we collate them into a map of relevance across the entire image. We use that map to identify the location of the object of interest. Here’s an example for detecting an orange:

Once we have identified the location of the object, we can recreate a bounding box around the object given a threshold for classification score. To achieve this, we used a RealSense D435i camera to obtain depth information, which we combined with the center of the object bounding box produced by CLIP to obtain 3D location information for the object.

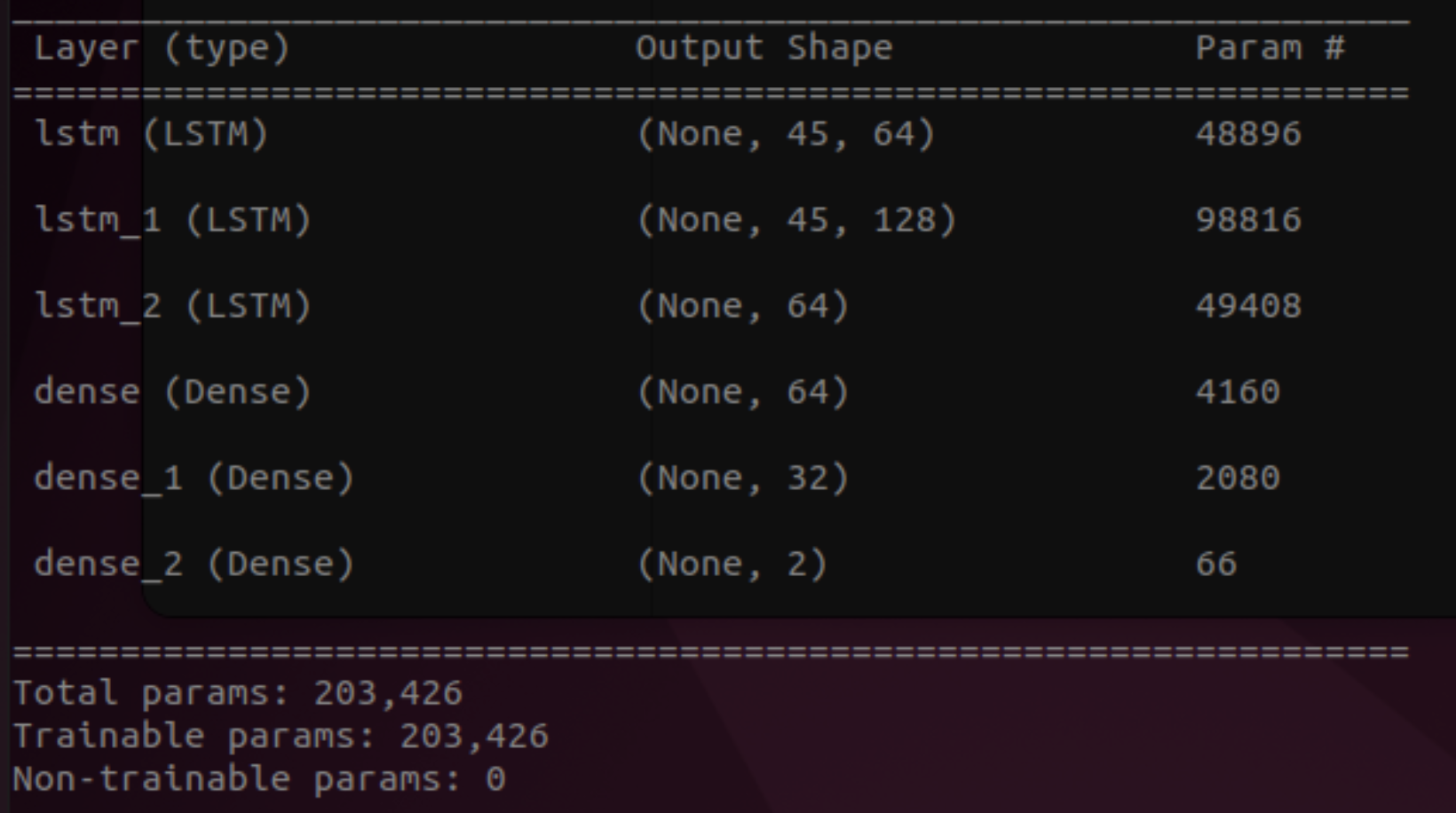

Hand Action Recognition with MediaPipe & LSTM

For more complex recipes that require human collaboration, our system needs to be able to recognize when the user has completed their assigned task. To address this, I developed a hand action recognition module using MediaPipe and an LSTM neural network. Since it’s difficult for a single robot arm to perform tasks like cutting vegetables, we rely on the user to complete these tasks. However, we need a way to provide feedback to the system once the user has finished executing their tasks. To do this, I collected labeled video data and trained the LSTM neural network to classify video clips into hand actions such as grabbing and cutting behaviors. Instead of feeding entire video sequences into the neural network, I used MediaPipe to extract hand landmarks for faster processing and dimension reduction. Each video frame contained 21 hand landmarks with 3D coordinates. I collected 60 video clips for each hand action class, where each clip contained 45 frames. The LSTM was trained with categorical cross-entropy loss for 20 epochs and achieved 100% accuracy on the small testing set I collected. The architecture of the LSTM model is shown below:

The below video demonstrates the hand action recognition model in action.

Motion Module

The motion module of the system is built on top of a custom Python MoveIt API that my team and I built for controlling the Franka Emika Panda robot arm in a previous project. The API provides an interface to control the robot arm with a simple Python script by specifying Cartesian positions. In this current project, I used the same API to control the robot arm to perform the various actions required in the recipe. For example, given the position of an ingredient, the API can move the end effector of the robot arm to that position and perform the appropriate action, such as picking up or placing the ingredient. The API also provides collision detection and avoidance capabilities, ensuring the robot arm does not collide with any other objects in the workspace. By building on top of this existing API, I was able to rapidly prototype the motion module of the system and focus on the integration with the other modules.

Source code

Reference

- Ahn, M., Brohan, A., Brown, N., Chebotar, Y., Cortes, O., David, B., Finn, C., Fu, C., Gopalakrishnan, K., Hausman, K., Herzog, A., Ho, D., Hsu, J., Ibarz, J., Ichter, B., Irpan, A., Jang, E., Ruano, R. J., Jeffrey, K., … Zeng, A. (2022). Do As I Can, Not As I Say: Grounding Language in Robotic Affordances. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2204.01691

- Lugaresi, C., Tang, J., Nash, H., McClanahan, C., Uboweja, E., Hays, M., Zhang, F., Chang, C.-L., Yong, M. G., Lee, J., Chang, W.-T., Hua, W., Georg, M., & Grundmann, M. (2019). MediaPipe: A Framework for Building Perception Pipelines. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1906.08172

- Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S., Sastry, G., Askell, A., Mishkin, P., Clark, J., Krueger, G., & Sutskever, I. (2021). Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2103.00020