Action Chunking with Transformers (ACT) for Assistive Action Prediction

This project explores end-to-end visuomotor policies to enhance human-robot collaboration using Omnid mocobots - a novel class of mobile collaborative robots designed for safe and intuitive co-manipulation of heavy or unwieldy payloads. Building upon the original Omnid platform, which uses passive compliance and force control to make payloads feel weightless during human interaction, we investigate how modern generative methods can make this collaboration even more seamless. By implementing and comparing two state-of-the-art approaches - Action Chunking with Transformers (ACT) and RGB-Diffusion Policy - we develop systems that can predict and generate assistive robot actions based on visual and force feedback. Our goal is to minimize human effort in co-manipulation tasks by enabling the robots to better understand and anticipate human intent. The project encompasses a complete pipeline from ROS2 infrastructure development and data collection to model implementation and real-world evaluation.

Video Demo

Prior Work: Omnid Mocobots

Part I: Migration from ROS1 Melodic to ROS2 IRON

To take advantage of the new features ROS2 provide, we transitioned 14 ROS1 Melodic packages over to ROS2 Iron. Here are some of the key steps we took:

- Adapting Source Code: Updated the original code to incorporate ROS2-specific libraries like rclcpp.

- Build System Modification: Adjusted packages to ensure compatibility with the ROS2 build system and its accompanying tools.

- Updating Definitions: Updated message, service, and action definitions to be in line with ROS2 requirements.

- Parameter Definition Updates: We made changes based on the structural shift from ROS 1 to ROS 2. While ROS 1 parameters are tied to a central server facilitating runtime retrieval via network APIs, ROS 2 places parameters on a per-node basis, making them adjustable in real-time through ROS services.

- Docker Environment: Set up a Docker environment integrated with Ubuntu 22.04 and ROS2, allowing for hardware testing.

- Unit Test Compatibility: Revised unit tests for ROS2 compatibility. Notably, my partner Nick did exemplary work in this area – you can view the specifics of our approach with the catch2 testing framework for ROS2 here.

- Remote Launch: This is an innovative ROS2 package that empowers users to remotely initiate nodes and launch files via SSH. You can view the work done by my partner Nick on this here.

Part II: Integrating ros2_control into Omnid

The motivation behind our venture into ros2_control integration can be distilled into two reasons:

-

Modularitywith ros2_control: ros2_control lets users deconstruct robotic systems into more straightforward, swappable components. Termed as “hardware interfaces,” these components provide a plug-and-play capability. This becomes particularly useful when there’s a need to substitute a specific hardware module or modify a control algorithm without overhauling the entire system. -

Dynamic Reconfigurability: The framework offers an array of tools that facilitate the dynamic loading, unloading, initiation, and cessation of controllers during runtime. Such dynamic adaptability proves invaluable during developmental phases, offering rapid iterations, and operational stages, adjusting to evolving conditions or tasks.

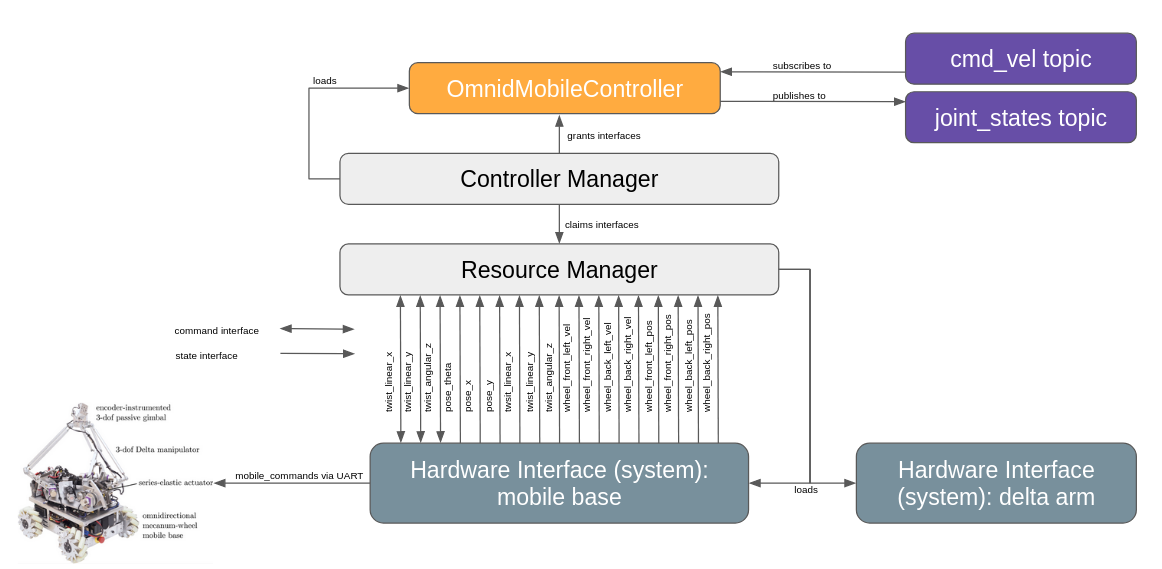

However, integrating ros2_control posed a significant challenge. Our existing system had abstracted the chassis control down to its embedded microcontroller. While our microcontroller responded directly to a twist command, ros2_control mandates direct hardware access to each motor’s position, velocity, and effort control. Our workaround was to conceptualize the entire base as a singular joint, manipulated via three velocity interfaces: twist linear x, twist linear y, and twist angular z. Here’s a diagram of our ros2_control architecture:

Part III: Data Infrastructure for Machine Learning on Omnid

Setup

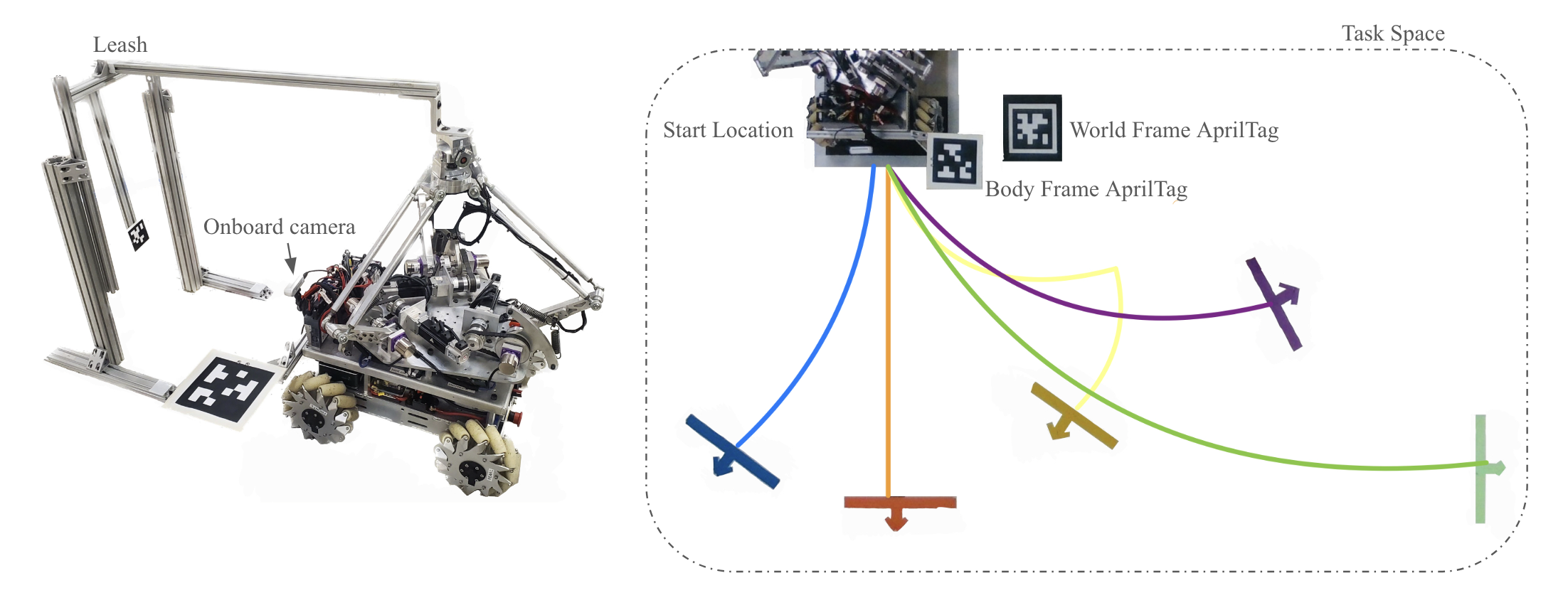

For our task, we added a rigid leash to the end effector of the original omnid robot, so that we can maintain a safe distance from the robot when collecting data. To ensure that the robot’s end effector is in the same position at the start of each data collection, we also created a rack to place the leash. In our task space, we placed five goal locations marked with color tape. In the image below, we can see there are five goals in blue, orange, yellow, purple, and green, each with a unique orientation and location.

Our data collection includes not only the robot’s own data, such as commanded velocity and joint states, but we also placed two external cameras: one overhead camera fixed to the ceiling and one horizontal camera fixed on a table next to the task space. Additionally, we equipped the robot with an onboard camera facing the direction of the human operator. All three cameras are RealSense D435, but we only used their color stream. The point is that if in the future someone wants to generalize or replicate our approach, it’s not necessarily required to use depth cameras. Ideally, even low-cost webcams could be used. In our data collection, we require the human operator to move the robot from the start location to one of the goal locations. The gif below (generated with Foxglove) shows one demo run with video streams from the three cameras described above and the force magnitude on the end effector over time.

Data Collection

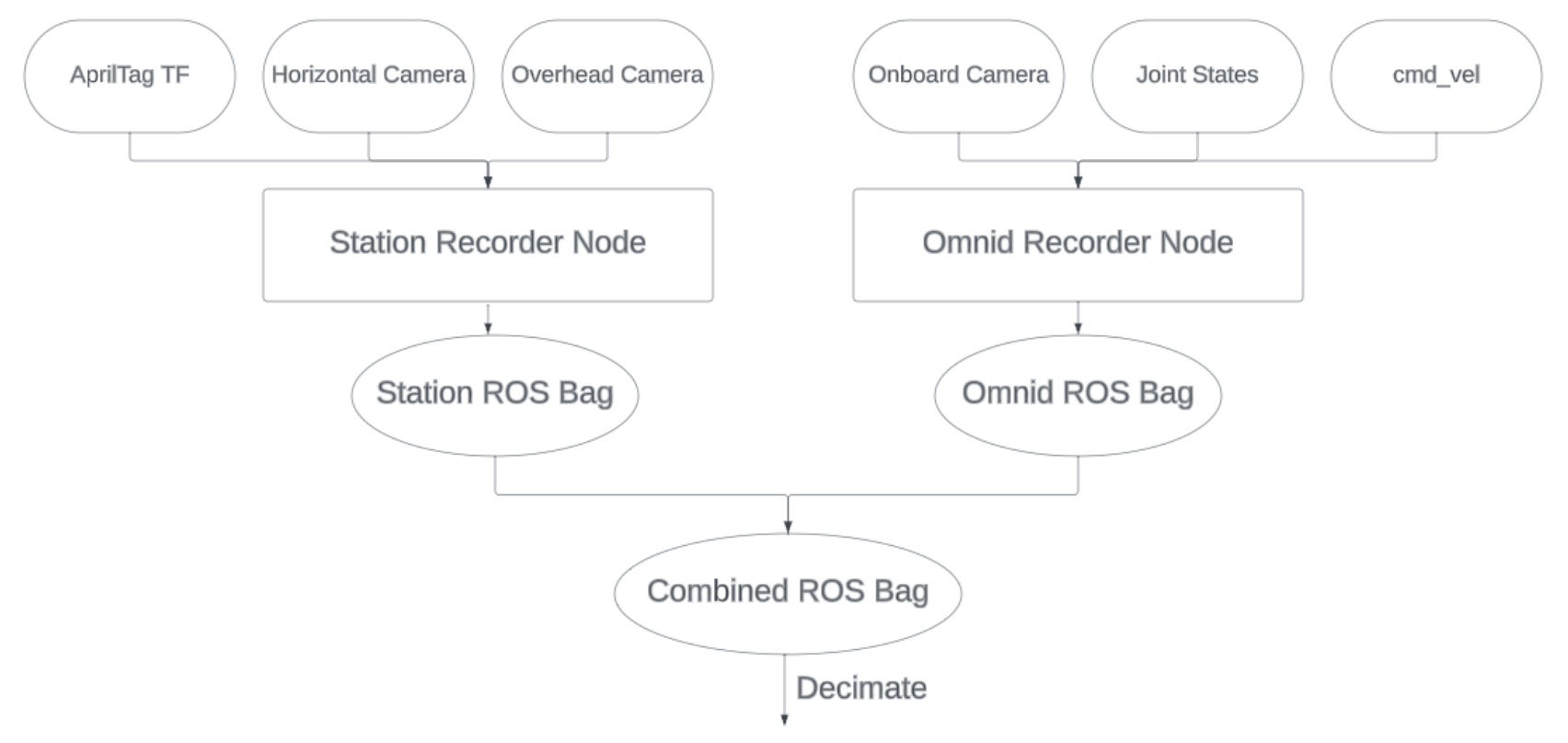

For data collection, we used ROS bags to record the necessary data. Due to the limited data transfer speed over the wifi network, which couldn’t meet our required rate, we recorded simultaneously on both the station (the computer running the ROS launch file) and the omnid robot during each recording session. Afterwards, we merged the data from both sources. On the station, we recorded data from the two external cameras and AprilTag, while on the omnid, we recorded from the onboard camera and the robot’s own data. To accelerate our data collection process, we developed a ROS2 package named omnid_data_collection. This package can launch all the necessary nodes, record based on the topic names we specify, and includes a bash script that simplifies user interaction with the entire process to a series of ‘enter’ commands. The package’s launch file utilizes Nick’s launch_remote_ssh package to simultaneously launch nodes on both the station and the omnid. Thanks to this series of process optimizations, we managed to reduce the time to record each demo to about 40 seconds.

Visualization

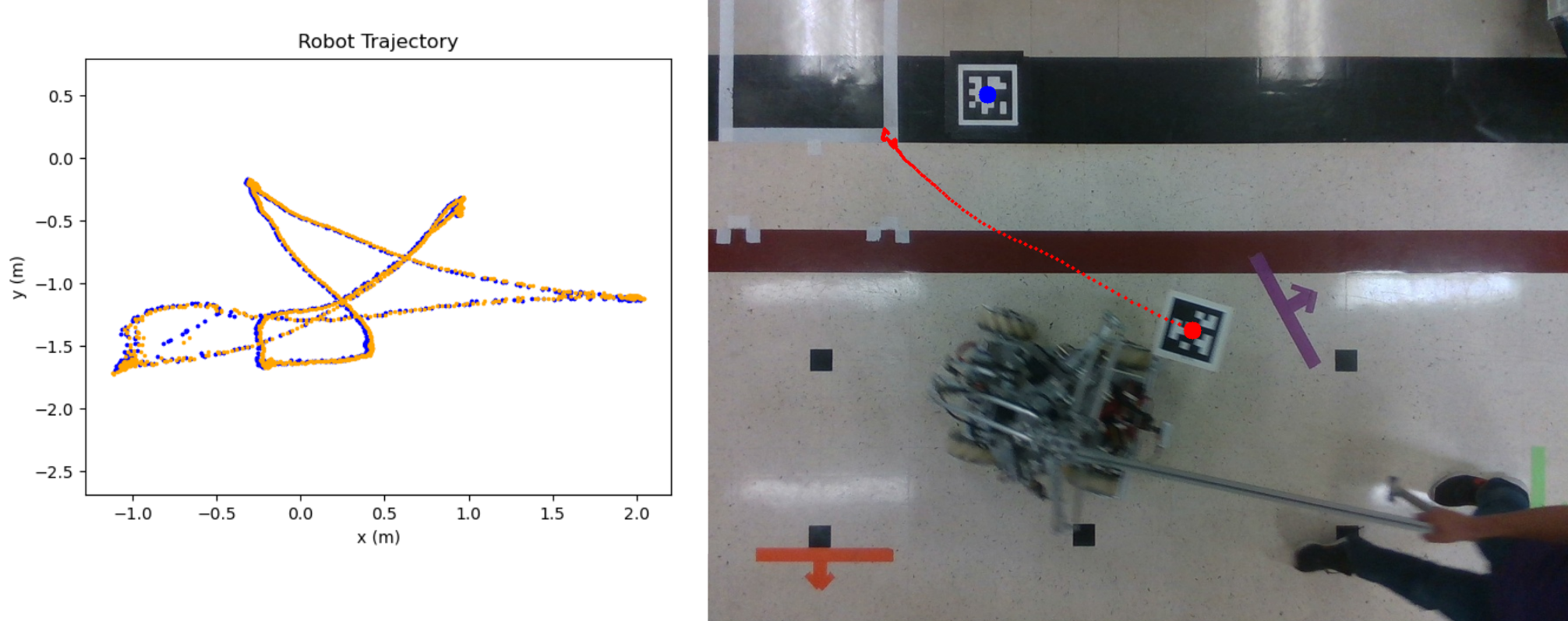

To ensure that we can easily understand what happens in each run, we also wrote some visualization utilities in the omnid_data_collection package. For example, the following is a visualization of AprilTag tracking. We calculate the trajectory traversed by the omnid by computing the difference between the world frame AprilTag and the base frame AprilTag tracking.

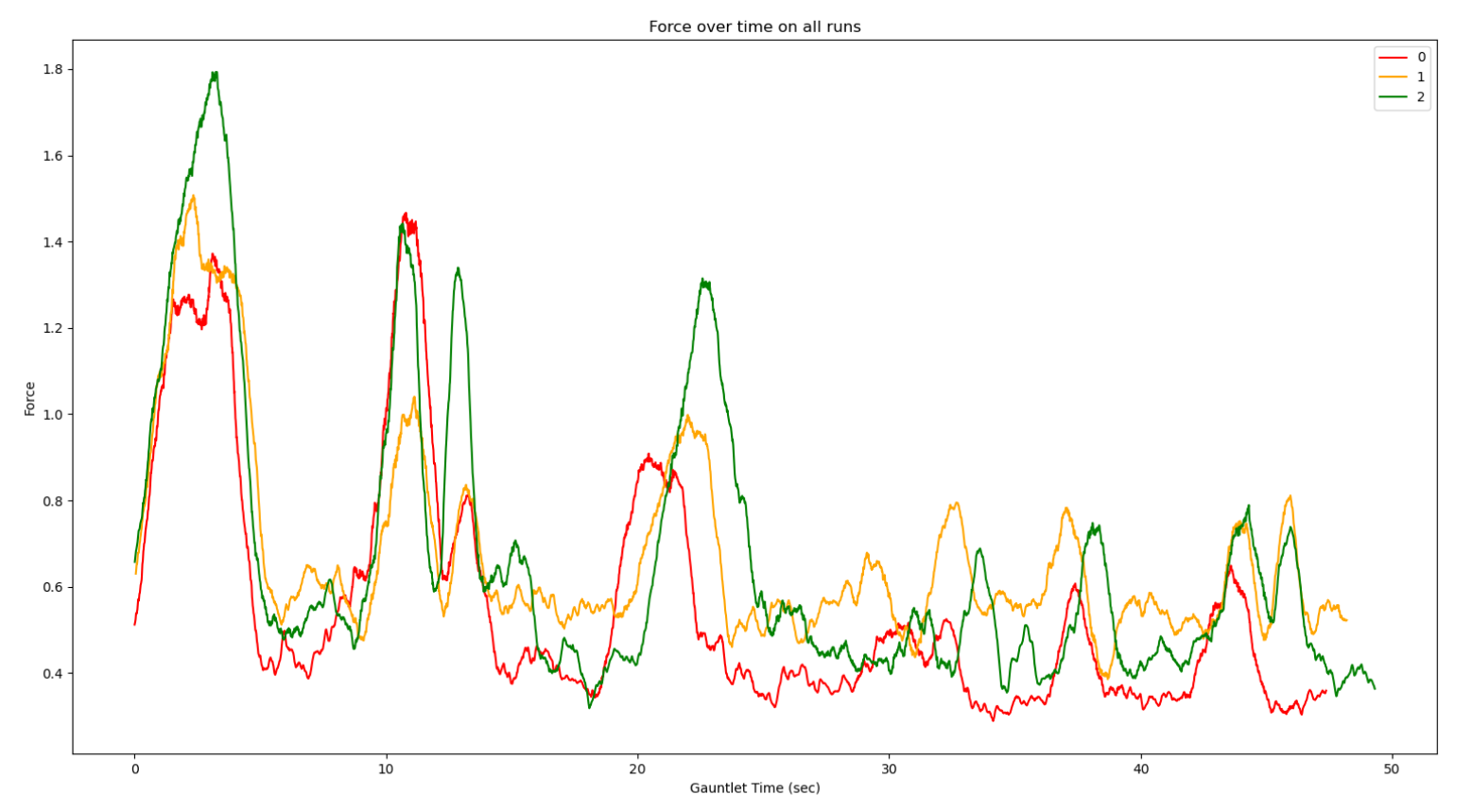

Besides caring about the path of the omnid, we are also interested in the net force magnitude over time on the x and y directions (planar) on the end effector. Therefore, as shown in the image below, we have a plotting utility that compares the force magnitude.

Part IV: Imitation Learning for Assistive Action Prediction

Prior work on the omnids has empowered humans to collaborate seamlessly with robots, enabling effortless manipulation of sizable and weighty payloads through gravity compensation and passive compliance. Building on this, our current project aims to further simplify this co-manipulation process by “inferring” human intent. To do this, we’ve adopted two State-of-the-Art robot learning approaches:

The objective is for the robot to autonomously apply supplementary forces on the end effectors, allowing humans to exert less effort. While my partner Nick works with the Diffusion Policy, I’ve been working on the Action Chunking with Transformers approach. To understand how the Action Chunking with Transformers approach works, we first need to understand the Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE).

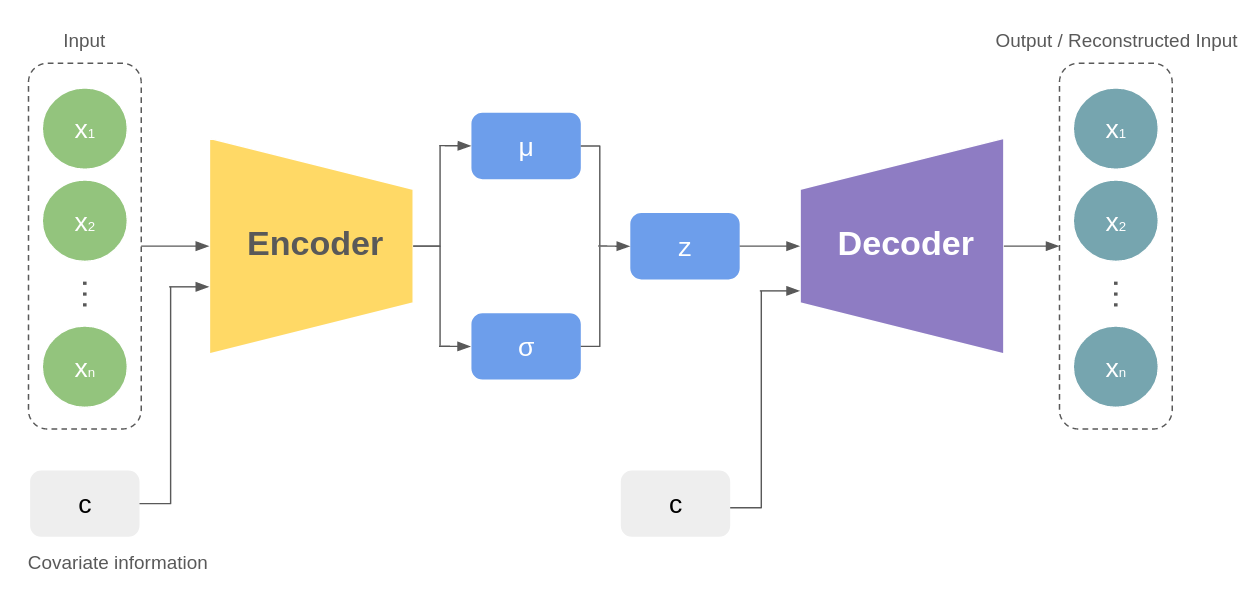

Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE)

A simpler version of CVAE, Variational Autoencoder (VAE), is a type of generative model that encodes data into a probabilistic latent space representation and then decodes it back to the original space. It uses an encoder to map input data to a probability distribution in latent space and a decoder to reconstruct data from this space. A Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) extends this concept by conditioning the latent space representation on additional information, like labels. This conditioning allows CVAEs to generate data specific to given conditions, enhancing the control over the generation process.

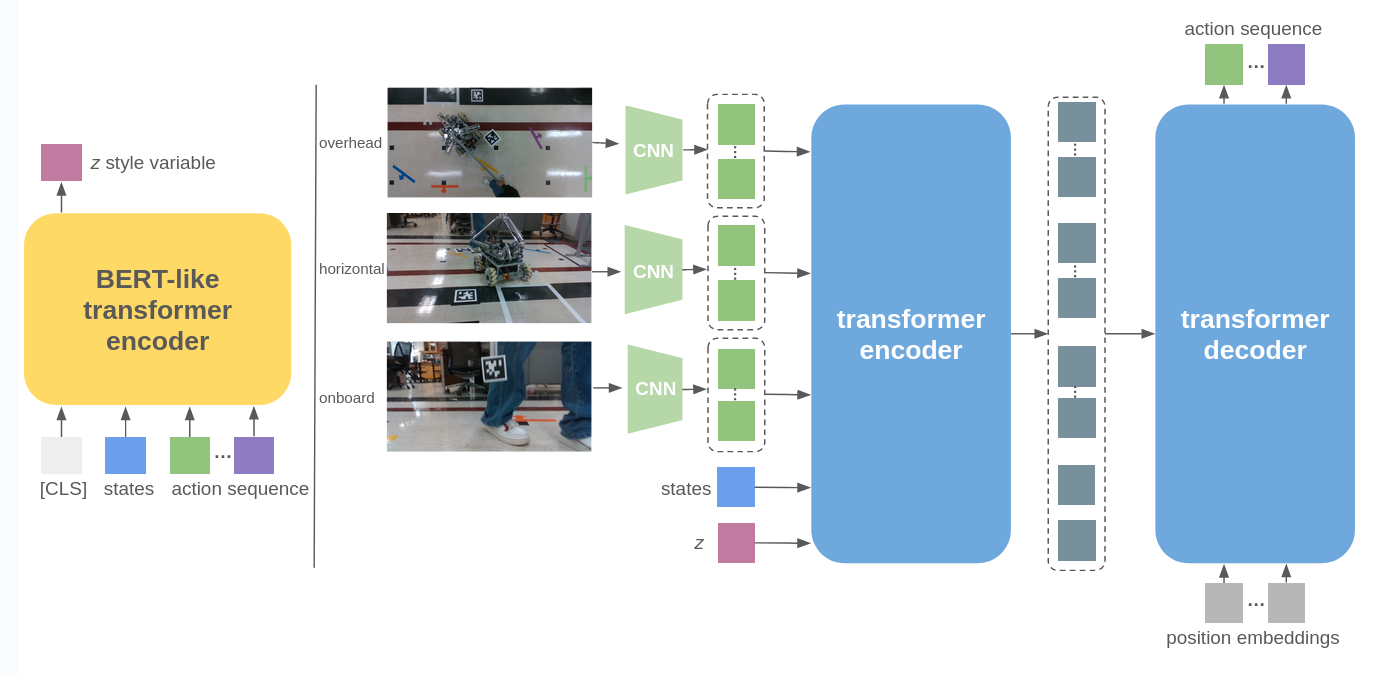

Action Chunking with Transformers

In the implementation of the CVAE architecture within the ALOHA work, it also incorporates an encoder and a decoder. The encoder here is a BERT-like transformer encoder, with inputs being 1) current robot states, 2) k (chunk size) action sequence of the demonstration, and 3) a learned [CLS] token similar to BERT. After passing through the encoder, only the token corresponding to [CLS] is retained to predict the mean and variance of the “style variable” z, which is then used as input to the decoder.

The decoder in this architecture takes 1) camera data, 2) current robot states, and 3) the style variable z to output the next k actions. ResNet serves as the backbone CNN for processing images from the camera. Within this CVAE decoder, there is also an encoder and a decoder, both implemented using transformers. In simple terms, the transformer encoder synthesizes information from different camera viewpoints, the robot states, and the style variable, while the transformer decoder generates a coherent action sequence. After processing image data with ResNet, to retain spatial information, a 2D sinusoidal position embedding is added to the feature sequence. The transformer decoder conditions on the encoder output through cross-attention, where the input sequence is a fixed position embedding. A notable aspect of this work is the use of L1 loss for reconstruction instead of the more common L2 loss, as L1 loss leads to more precise modeling of the action sequence.

During training, both the encoder and decoder are utilized, but during evaluation, we discard the encoder and solely use the decoder to output the action sequence.

Specifically for our task, we collected 50 demonstrations for each goal location, giving us 250 demonstrations in total.

Below is an architecture diagram illustrating the adapted Action Chunking with Transformers policy, inspired by the ALOHA paper:

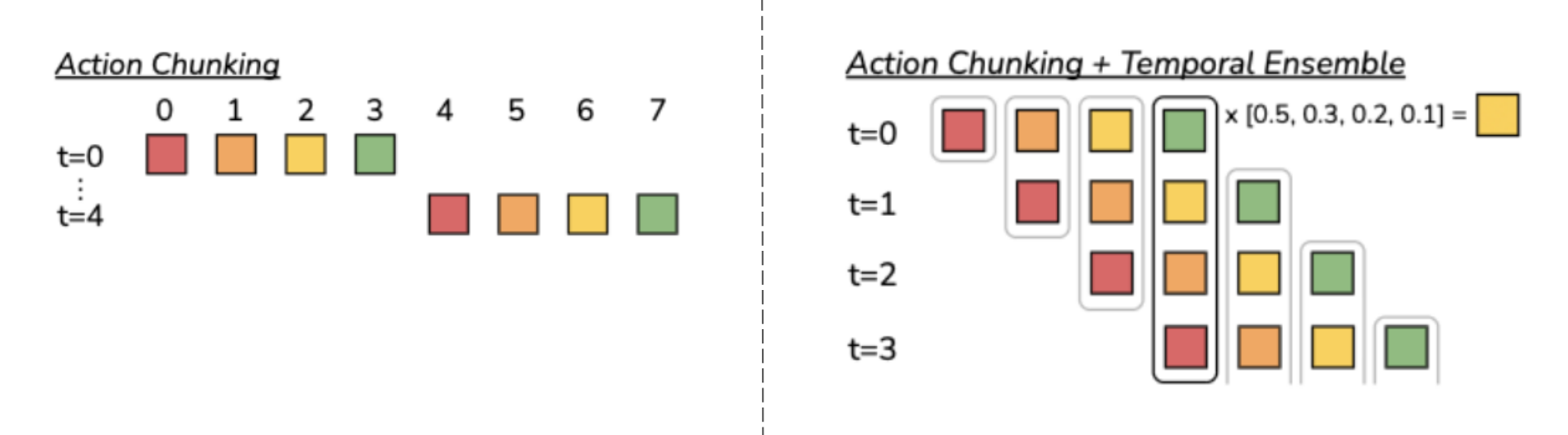

One unique feature of this work is named action chunking with temporal ensemble. To address the errors in imitation learning and efficiently implement pixel-to-action policies, action chunking (inspired by neuroscience) is adopted, where actions are grouped and executed in units (chunks). This reduces the effective horizon of tasks and allows the model to handle non-Markovian behaviors in human demonstrations. To enhance smoothness and avoid jerky motions, action chunks are overlapped by querying the policy at every timestep and using a temporal ensemble method, which averages predictions with exponential weighting. This approach results in precise and smooth predicted motion without additional training costs, only increasing inference-time computation.

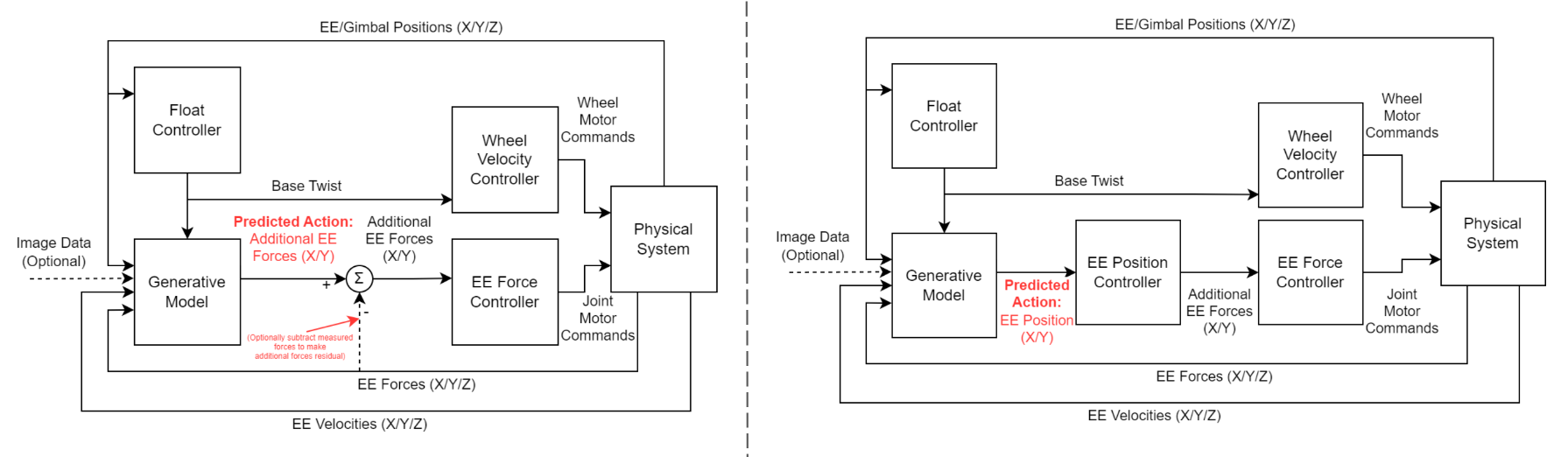

Control Modes

To implement this architecture with the Omnids, we’ve developed two control modes: 1. Predicting additional forces to be applied on the end effector and apply that amount of force. 2. Predicting the end effector’s position and actively moving towards that position. Below are the diagrams for our two control modes, with the left being force control and the right being position control:

Evaluation

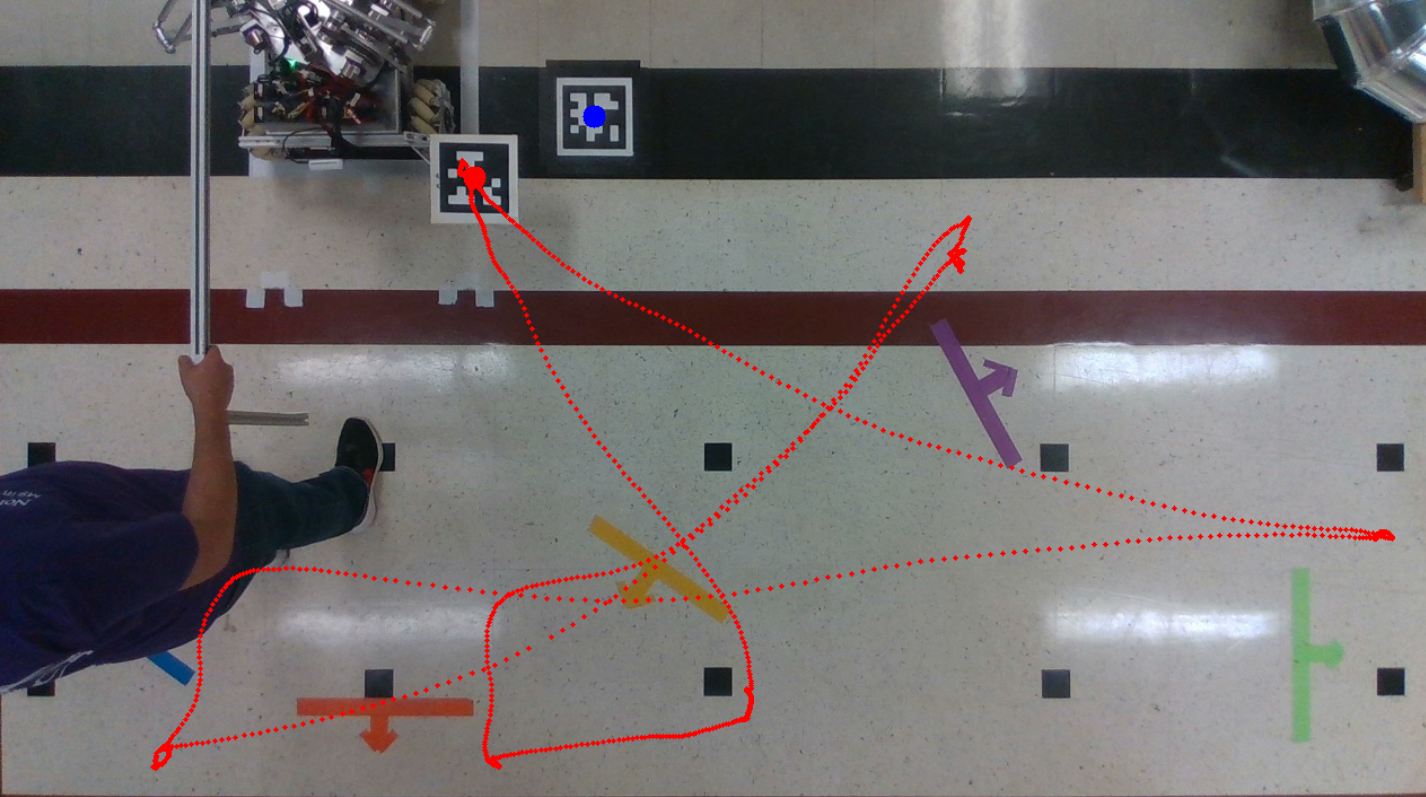

To evaluate whether our approach makes it easier for the human operator to complete co-manipulation with the Omnids, we designed a task called the Gauntlet Game, where we lead the omnid through five target locations and record the completion time. At each target, we need to ensure the omnid is within a certain distance threshold and stays there for a set amount of time. This is achieved through visual feedback monitored by AprilTag tracking on the side. We came up with two metrics to measure our approach: the average time to complete the Gauntlet Game, and the average force magnitude. The image below shows the tracking trajectory of one such Gauntlet evaluation, provided by AprilTag.

Results

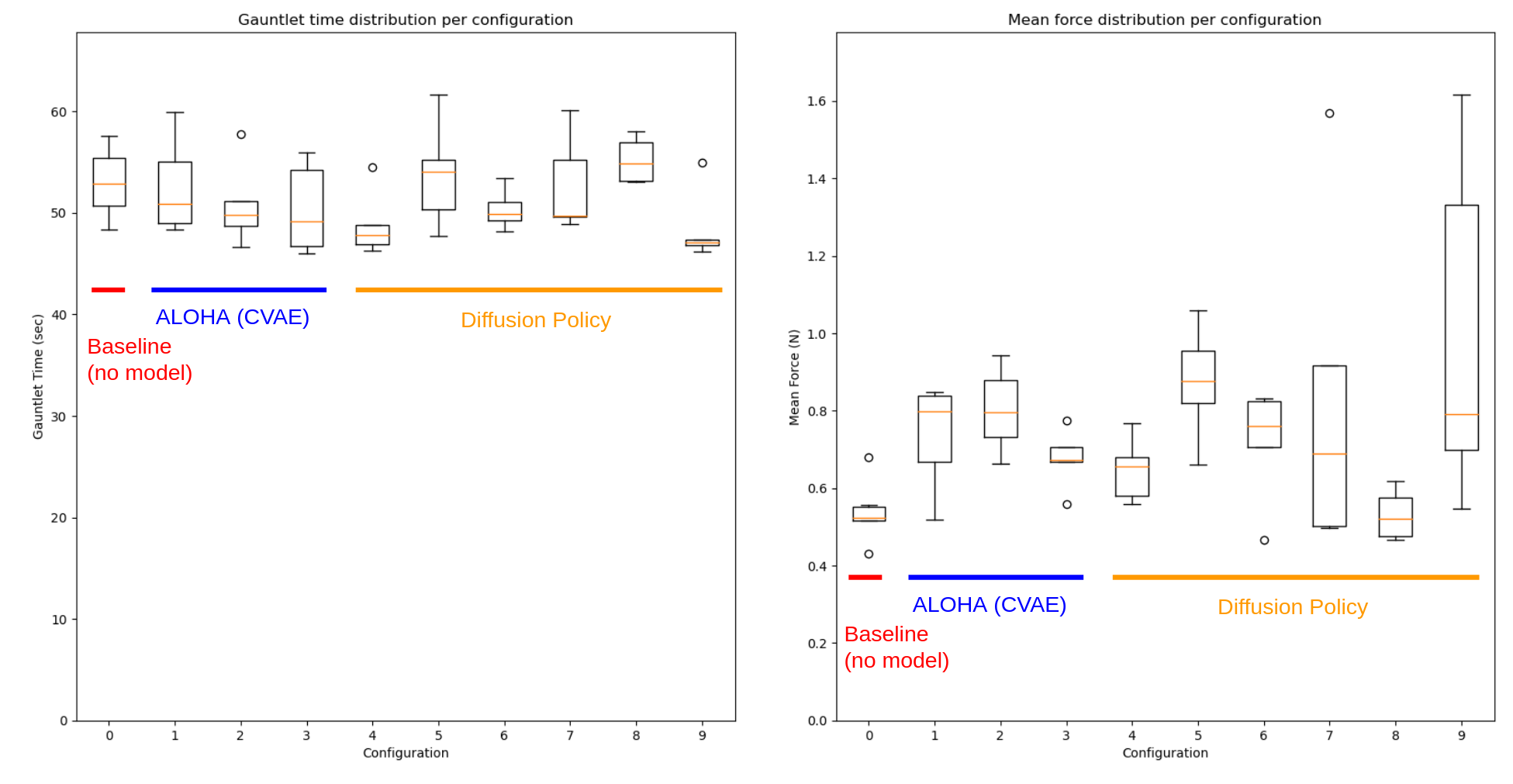

The image below contains the evaluation results of the baseline, CVAE, and Diffusion Policy using the gauntlet game, with the left side showing completion time and the right side showing average force. Each type of model has many different configurations, and the specifications for each configuration is provided below the image.

- NONE - None

- CVAE - action chunk size = 10

- CVAE - action chunk size = 5

- CVAE - action chunk size = 20

- DIFFUSION - image, ee_gimbal, cmdvel, Tp16, To2, Ta8, K16

- DIFFUSION - lowdim, ee_gimbal, cmdvel, Tp128, To32, Ta32, DDIM, K16

- DIFFUSION - lowdim, ee_gimbal, Tp128, To32, Ta32, DDIM, K16

- DIFFUSION - image, ee_gimbal, Tp16, To2, Ta8, K16, RES

- DIFFUSION - image, ee_gimbal, Tp16, To2, Ta8, K16

- DIFFUSION - image, ee_gimbal, cmdvel, Tp16, To2, Ta8, K16, RES

Looking at these plots, there is a slight improvement in the completion time for the gauntlet game. We can observe that some CVAE and diffusion policy models achieved a lower median completion time compared to the baseline. However, the average force exerted by nearly all models was significantly higher than the baseline. We believe this result is reasonable, as if our model exerts the predicted force on the end effector and the human operator continues to add force, the total force should indeed be higher than the baseline. This is further supported by the fact that there’s an improvement in time since a higher total effective force should lead to faster completion of the gauntlet task.

Future Work

One thing that we began to experiment with but didn’t have the time to test in-depth is the idea that if we train our policy to learn multiple goals, just like what we are doing now, the policy is learning multiple tasks and might not always make effective predictions at some arbitrary locations. Therefore, we tried training our policy on a single target location and obtained promising results, where we observed significantly shorter completion times with our models than using the baseline. Additionally, we considered that instead of indirectly controlling the motion of the omnid, we could try directly replacing the PID controller in the original system, which centers the delta arm end effector on the chassis. Eventually, if these models show promising results in simpler single robot tasks, we could attempt to generalize these approaches to a swarm of three omnids to perform assembly tasks.

Group Members

Nick Morales, advised by Prof. Matthew Elwin

Source Code

Reference

- Elwin, M. L., Strong, B., Freeman, R. A., & Lynch, K. M. (2023). Human-multirobot collaborative mobile manipulation: The Omnid Mocobots. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 8(1), 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1109/lra.2022.3226366

- Zhao, T. Z., Kumar, V., Levine, S., & Finn, C. (2023). Learning Fine-Grained Bimanual Manipulation with Low-Cost Hardware. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.13705. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.13705